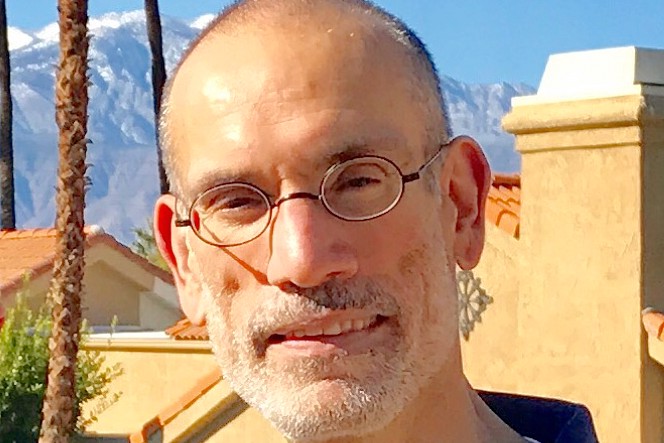

In the midst of student protests over racism nationwide and on campus, Barry D. Amis helped found the Black Student Alliance at Michigan State University in 1967 and served as its first president. He has notebooks filled with news clippings and photos from his years as a student activist.

“What we did at the time at MSU was groundbreaking,” said Amis, who earned a Ph.D. in Spanish from MSU in 1970.

As a doctoral student living in Owen Hall in 1966, Amis was struck by the friendliness of the campus, but the lack of diversity among students, faculty, and staff was obvious. One area of meaningful integration, he noted, was the MSU Football program. Since the late 1950s, Head Coach Duffy Daugherty had worked to integrate college football by recruiting Black athletes from the South who were barred from playing at many Southern schools.

“While there were a thousand or more international students at MSU, from what I could see, there were only about 400 Black students,” Amis said. “That struck me the wrong way and seemed ludicrous at a university of about 40,000 students.”

“While there were a thousand or more international students at MSU, from what I could see, there were only about 400 Black students. That struck me the wrong way and seemed ludicrous at a university of about 40,000 students.”

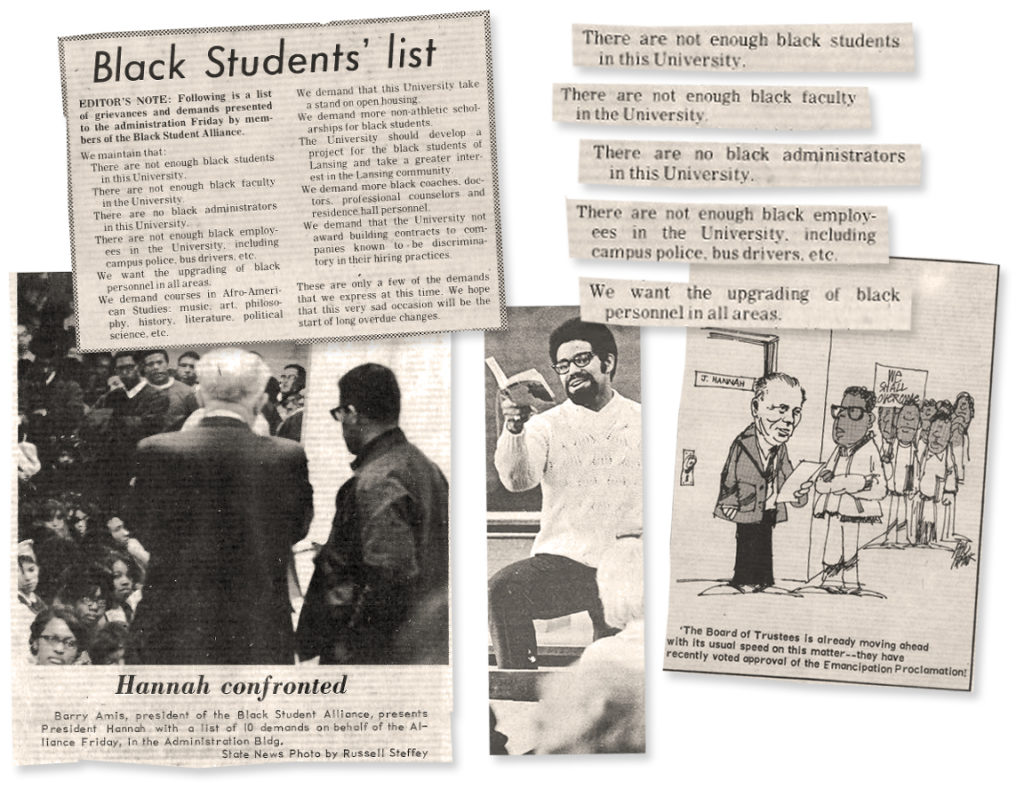

Amis learned about an initiative to bring a small cohort of 25 Black students to MSU. He felt the effort was insufficient given that Black people comprised about 10 percent of Michigan’s population. He wrote a letter to the editor of The State News lambasting the program as “tokenism.” Among those who read the letter was President John Hannah who invited Amis to come and chat about his concerns.

Founding MSU’s Black Student Alliance

Motivated by the reaction to his letter, Amis and others set out to form a group for Black students. Associate Professor of Education Robert L. Green served as faculty lead and opened his home for a core group of 12 to 15 students to meet and organize the Black Student Alliance (BSA), a group still active to this day. Green himself was a national civil rights leader who became one of the first Black homeowners in East Lansing after legally challenging the city’s practice of redlining.

On April 4, 1968, Amis’ activism ignited with the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was in his room studying when a fellow student called him to come outside and join a group of several hundred Black students. They were angry. They wanted to do something. With fellow members of the BSA, Amis helped organize a protest.

“We knew other student groups like the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) were holding demonstrations across the country and occupying buildings,” he said. “We decided on the Administration Building and occupied it overnight, with a plan to author a list of demands.”

That evening, Amis and the BSA drew up a list, demanding the university take action to make the history, culture, and participation of African Americans a more integral part of the MSU environment. They started with the assertion that there weren’t enough Black students, faculty, administrators, and staff at MSU. The group demanded that MSU offer courses on African American Studies and take a stance on open housing. Additional demands included more non-athletic scholarships for Black students; the development of a project with Lansing’s Black community; more Black coaches, counselors, and residence hall staff; and the cessation of building contracts to companies with discriminatory hiring practices.

“For all my concerns at that time about Black and minority programs, I recognize what Hannah did for the university. He was a remarkable man. He built the modern MSU.”

The next day, Amis and Green led members of the BSA on a march through campus. As they wound their way down West Circle Drive and other streets, the march swelled to nearly 2,000 students. Following the march, Amis and the BSA delivered the list of grievances to MSU administration and later met with President Hannah, who was quick to point out that he had invited Amis to meet just a year before.

“For all my concerns at that time about Black and minority programs, I recognize what Hannah did for the university,” Amis said. “He was a remarkable man. He built the modern MSU.”

Educator of the Black Experience

Amis’ activities with the BSA caught the attention of the campus community. He was frequently invited to speak in classes about the Black experience and the contributions of Black Americans. He also was invited to share his ideas on the formation of programs and curriculum focused on Black history and literature.

“Many students were unaware of Black writers, artists, and scientists,” Amis said. “They weren’t aware of the scope of Black literature or the arts. Some simply saw Black contributions to society through their knowledge of the occasional athlete.”

All along, Amis continued to lead protests with the BSA, including a sit-in at the Wilson Hall cafeteria, charging “overt racism” in the treatment of three Black employees. He participated, too, in campus-sponsored forums designed to mitigate institutional racism at the university and wrote editorials for The State News. As a more experienced activist, Amis developed productive relationships with successive MSU presidents and faculty, who, in turn, recommended him for scholarly posts.

In 1969, Amis joined the MSU faculty as an Assistant Professor of English and Romance Languages. He simultaneously finished his doctorate, while teaching beginning Spanish and contemporary African American Literature, a course he developed.

While he enjoyed teaching, Amis still wanted to pursue his long-time desire to work and travel abroad. He applied to the Fulbright Scholar Program and received a grant to teach American Studies in France at the University of Caen. The award was the first of three Fulbright grants that led to teaching in Madagascar, Cameroon, and Niger at multiple universities. He also lectured and conducted workshops in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East through the United States Information Agency. After six years abroad, Amis returned to the United States to teach at Purdue University, conduct staff development with a national teachers’ association, and oversee staff development initiatives for Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland.

Parental and Sibling Influence

Looking back on his life, as he sifts through newspaper clippings at his home in Alexandria, Virginia, the now 80-year-old Amis puts his activities and accomplishments into context by thinking not of himself, but rather his parents and siblings.

“I viewed my activities at MSU as a continuation of the struggle for workers’ rights and racial justice of my father and the civil rights activities of my sisters in the South,” he said.

Amis thinks back to the days that preceded his life as an MSU doctoral student and faculty member. He recalls growing up in Philadelphia and his dreams of traveling and living overseas. Most of all, he remembers his parents and how their passion for Black and working-class causes shaped his life, as well as the lives of his sisters who went on to become committed civil rights activists.

“When you’re a child, especially working class, you never really think of your parents as special,” Amis said. “But as I grew older and attended high school and college, I realized what my parents had actually done and how significant it was.”

Amis’ father, B.D. Amis, was a Black activist and labor organizer in the late 1920s and 1930s. Born in Chicago, B.D. Amis was among a group of African Americans who led the fight for workers’ rights and racial justice. A writer, speaker, and leader, B.D. Amis headed a chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Peoria, Illinois, in the late 1920s. Later, in the 1930s, he was one of the first native-born and working-class Black leaders of the Communist Party USA and General Secretary of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights.

“When you’re a child, especially working class, you never really think of your parents as special. But as I grew older and attended high school and college, I realized what my parents had actually done and how significant it was.”

Amis remembers attending party meetings with his dad as a youngster in Philadelphia. W.E.B. DuBois, one of the founders of the NAACP, stood out at one meeting, mostly because he wore a three-piece suit when others dressed in work clothes. Paul Robeson was another colleague his father had known for decades because of their shared interest in workers’ rights. Amis also recalls how party leaders, friends, and activists frequently visited their home.

“There were always people coming by the house to see my father,” Amis said. “Later on, college professors and historians came by, too. My father kept a lot of papers and documents, some of which are now in university libraries.”

In 1950, B.D. Amis moved his family from public housing in North Philadelphia to a row home in West Philadelphia. At that time, the Amis family was the second Black family on the street. Within five years, the street went from being all white to all Black through the practice of “block busting.”

That experience, along with the racism he saw levied against baseball heroes such as Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, further shaped the young Amis’ perceptions. As he grew older, he learned about other racially charged incidents, including the 1944 Philadelphia Transit Workers Strike, and the more he learned, the more he realized the importance of getting a good education.

“MSU has always been special to me because of the people I interacted with. It was just a great time to be there.”

“I became the academic in our family,” he said. “I was fortunate enough to attend Central High School in Philadelphia and get a good foundation that led me to other opportunities.”

Now retired, Amis writes poetry, builds on his published collection, and was a regional Vice President of the Poetry Society of Virginia. Most of the time, he’s content, particularly as he reflects on the big picture of his life and how MSU helped set his course.

“You can ask anyone of my neighbors where I went to school, and they’ll tell you MSU,” he said. “I wear MSU T-shirts all the time, and I’m an avid Spartan. MSU has always been special to me because of the people I interacted with. It was just a great time to be there.”

(Written by Kimberly Popiolek)